Anthony Leiserowitz

Director of the Yale Program on Climate Change Communication and a Senior Research Scientist at the Yale School of Forestry & Environmental Studies

The Day After Tomorrow in the news

Leiserowitz, Anthony A. “Before and After The Day After Tomorrow: A U.S. Study of Climate Change Risk Perception.” Environment, vol. 46, no. 9, Nov. 2004, pp. 22-37.

“The Long Melt: The Lingering Influence of ‘The Day After Tomorrow.’” Yale Climate Connections, 5 Nov. 2014.

The study

In 2004, soon after completing one of the first studies of American views on climate change, I started to see trailers for The Day After Tomorrow (TDAT). Immediately, I could see that it was going to be a Hollywood blockbuster that millions of Americans would watch, and it was going to describe climate change in a completely new way for the public.

At the time, a large part of the US population thought of climate change as a slow, incremental, linear process that might be a danger in the distant future. Recent climate science suggested this might not be the case; the climate system is highly sensitive and can reorganize abruptly, with consequences as potentially disastrous as the shutdown of the Gulf Stream. Interestingly, this premise was going to be envisioned in TDAT, so I immediately thought that this could be an amazing natural field experiment. I received support to conduct three national surveys: one, a week before the film’s release, another three weeks after, and a third four months later to see if there were long-term effects. We wanted to see if the film would have an impact on people’s beliefs, attitudes, policy preferences, and behaviors, and whether it would alter their perceptions of the risks of climate change.

We found that the people who saw TDAT were affected by it. Our results found that the film had a significant impact on the climate change beliefs, risk perceptions, policy priorities, behavioral intentions, and — by seemingly casting the Bush administration in a negative light — even the voting intentions of moviegoers.

The results

Our study made one thing clear: not only can narrative film have social impact, it can have social impact at scale. Period.

Even after controlling for demographic and political factors, people who saw the film became more convinced that climate change was real, became more worried about it, changed their conceptual model of how climate change actually works, became more supportive of climate policy, and became more willing to say that they at least intended to change their behaviors.

To cite a few results: 83% of moviegoers said they were concerned about global warming compared to 72% of non-watchers; more than 80% of moviegoers responded that global warming is likely to produce more intense weather events over the next 50 years, versus 72% of non-watchers; and perhaps most telling, moviegoers were more likely than non-watchers to believe that global warming could lead to a shutdown of the Gulf Stream current or a new ice age — two underlying premises of TDAT.

The Day After Tomorrow box office

“The Day After Tomorrow.” Box Office Mojo, IMDb.com, Inc.

https://www.boxofficemojo.com/movies/?id=dayaftertomorrow.htm

The power of story

Let me underscore this, because I can’t say it strongly enough: stories are one of the most powerful forms of communication that humans have invented. TDAT is, first and foremost, a story; stories provide us with an interpretation of reality and they are an incredibly powerful means to communicate ideas in an emotional way. Empathy and narrative transport helps people identify with characters, see through their eyes and share their experiences – and this is what makes stories such an effective tool for helping people to understand issues like climate change. Humans have always used narrative in this way, passing on essential, accumulated knowledge from one generation to the next, to aid with their very survival.

Furthermore, empathetic and vicarious experiences are one of the real opportunities of social impact entertainment. We love these experiences so much that we as filmgoers spent $40.6 billion in 2017 to put ourselves in dark rooms with strangers to watch them unfold! These stories shape our lives, they shape how we think about the world, and they can shape our identities.

The power of image

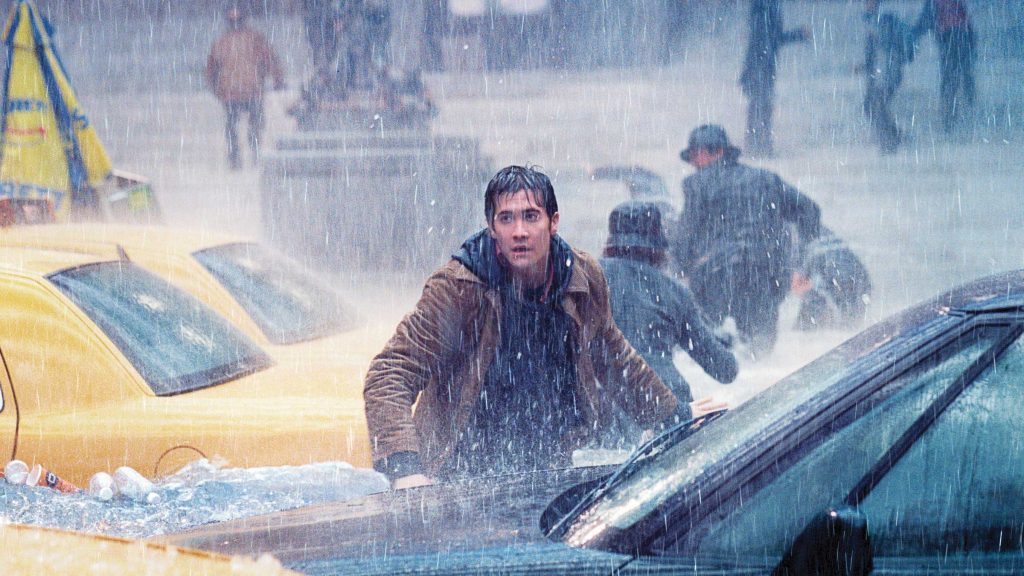

Perhaps more important than helping people experience the immediate threat of climate change was that TDAT provided people with images to actually imagine how climate change might impact us. For the first time, audiences had powerful, concrete images of the potential impact of climate change on American iconography. We weren’t just listening to someone talk about rising sea levels, we saw a tidal wave sweep through Manhattan. We didn’t just hear someone discuss extreme weather, we watched tornadoes rip apart LA.

One of the ideas underpinning our study was the cognitive-experiential self-theory (CEST), which was largely developed by Seymour Epstein and then furthered by other academics. In simple terms, CEST found that humans have two systems for processing information: the analytic and the experiential. The analytic is slow, deliberate, and rational, while the experiential — which is much older in evolutionary terms — is fast, intuitive, and emotionally driven. For many years Western science regarded the two systems as opposites, but by the time I began to study TDAT, we’d started to understand that they’re actually interwoven, informing each other.

It’s this deep, psychological understanding of the brain that helps to explain why a film like TDAT, with its incredibly rich and provocative images, can be such a powerful communication tool.

The teachable moment

Naturally, TDAT spurred a lot of viewers to seek out further information. Many organizations tried to leverage the film to advance the cause of tackling climate change, setting up websites to assist moviegoers who might have questions after seeing the film. Audiences did have questions, but most websites only launched on the day the film came out.

In a later study on what we called “the teachable moment,” we showed that an event planned for a specific release date (like a movie release) will generate increased information- seeking behavior before the event itself arrives. There is a specific period in the weeks prior to a film’s release where this ramp-up of public attention is at its peak, and this teachable moment is a critical time for people or organizations to strike while the iron is hot, before attention is diverted elsewhere. Naturally, it follows that filmmakers and organizations seeking to create maximum impact should have their outreach strategy in place well before the film’s release. For TDAT in particular, we found that the teachable moment spanned from 10 days before the release date to 19 days after.

TDAT was among the first films of its kind. While one film alone may not be enough to change the opinion of the entire public, it can certainly drive change at scale and help initiate or accelerate a culture shift, one where the momentum is continued by other projects. The audiences for TDAT accounted for 10% of the US population, and as we’ve seen, it had a quantifiable impact on people’s perceptions of climate change. However, it’s arguable that the film could have had even greater impact if change organizations had launched their websites in advance of the film, making the most of this teachable moment. By extension, this study emphasizes the importance of taking the right approach with social impact campaigns, tailoring your conversation to specific goals where possible, and engaging audiences at the most opportune moments before, during, and after release.

When a piece of entertainment speaks to the cultural and social dimensions of an issue it’s possible to change social and cultural norms — the unwritten rules of how people are supposed to behave — and thus effect big shifts in politics, policy, and society at large. That’s one of the real powers of popular culture and media: it can engage people in social issues in a way that is often more powerful than all the data, statistics, and scientific reports combined.

The Teachable Moment

Many environmental leaders and organizations described the release of The Day After Tomorrow (TDAT) as a “teachable moment” — an opportunity to use its themes and ideas as a springboard to educate the public about global warming, and perhaps even change policy.

Philip Solomon Hart and Anthony A. Leiserowitz’s paper Finding the Teachable Moment… explored how, if at all, the release of TDAT changed the information-seeking behavior of the public regarding “global-warming related websites.”

According to Hart and Leiserowitz, “In preparation for the ‘teachable moment,’ many environmental organizations created these websites based on the premise that TDAT and related media coverage would increase public information- seeking behavior.”

The team collected web-traffic data from six global-warming related websites from April 1st to June 30th 2004. The six were selected to represent a “variety of sources that provide information and/or advocate for specific policies to address climate change.” They included: a Johns Hopkins University website (EcoHealth); a website operated by the Union of Concerned Scientists (UCS); another operated by the Environmental Defense Fund (EDF); a website operated by the Global Exchange, Rainforest Action Network, and the Ruckus Society (RAN); a website operated by National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC); and one operated by the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute (WHOI).

Media coverage data of TDAT was gathered via a LexisNexis search between April 1st and June 30th 2004. The search was “limited to coverage from news sources, and included television, radio, prestige newspapers and major metropolitan newspapers.”

Of the websites studied, three (UCS, EDF, and RAN) were active throughout the duration of the study. The other three (EcoHealth. WHOI and NSIDC) launched on, or nearer to, the actual release date of TDAT (May 28th 2004).

For the first three sites, there was a clear spike in web traffic between May 12th and June 11th (Figure 1), clearly supporting the team’s hypothesis that “web traffic on global warming related websites increased during the release period of The Day After Tomorrow.”

The latter group comprising the three sites that launched closer to the release date of TDAT (EcoHealth, WHOI, NSIDC), showed similar results to the first group (Figure 2). However, the data also suggested that “by waiting until the movie release date to launch their respective The Day After Tomorrow websites, WHOI and NSIDC, in particular, missed the first week of heightened global warming related web activity that occurred during the ‘teachable moment’.”

Hart and Leiserowitz’s study and findings show that, despite being a fictional representation of the dangers of climate change, TDAT created a teachable moment of heightened public concern and increased information-seeking behavior. More specifically, as Leiserowitz and Hart write, “a ‘teachable moment’ of elevated information-seeking activity was found to extend from 10 days before the release date of The Day After Tomorrow to 19 days after the movie release date.